Introduced through gentle tones emanating from Makella Ama’s singing bowl, and then culminating with a poetry recital from Raheela Suleman, the director of SABR (2023) The Space Belongs To Them opens and closes through rhythmic sound.

The programme, expertly curated by Makella Ama and Sena Gikunoo at Rich Mix in Shoreditch for the second day of the London Short Film Festival, explores memory, movement through space and embodiment. The sounds instantly attune our senses to engage with the fullness of our living, breathing beings: to feel the subtle pressure of our bodies against the cinema seating, the hardness of floor to our feet, to dwell on the lives of our fellow audience members, the backs of their heads silhouetted by the screen’s dimmed glow.

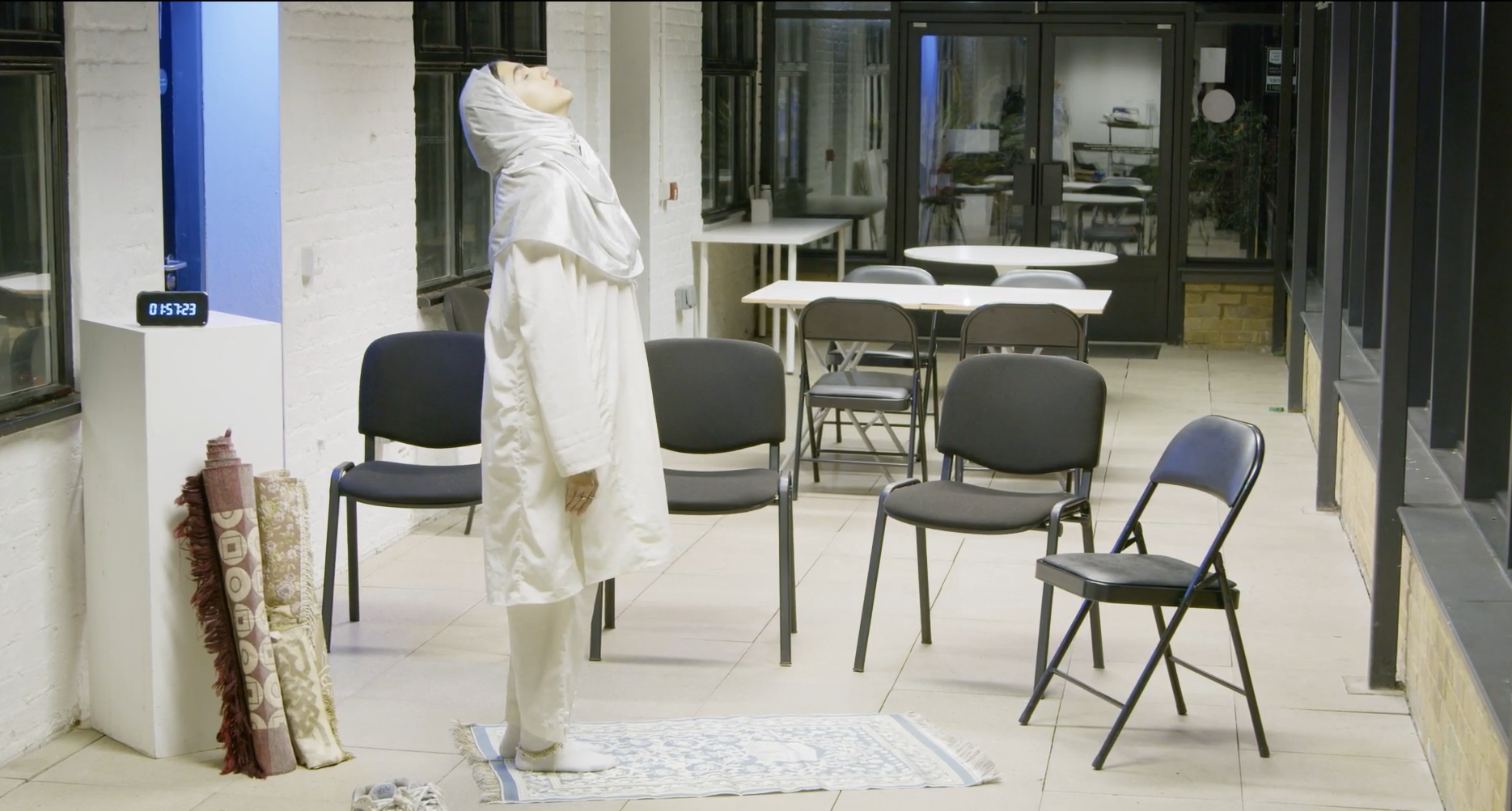

Screening mid-way through the programme, Nazif Coşkun’s Homeland/Welat (2014) presents a haunting view of a ruined, empty Kurdish village, where a continuous first-person shot and auditory memories of a bygone slow life of socialising and feeding farm animals echoes the days before its destruction. In the 11 minute runtime we’re wrenched out of place and no sooner do we digest the film’s unique commentary on the century-long, ongoing violent suppression of Kurdistan’s ethnic and political identity by the Turkish nation-state, are we shifted into the profound quietness of SABR (2023), which documents a woman performing salah in a private room, where, interestingly, the camera gaze impatiently whips from corner to corner, almost as if the act of prayer is too sacred for our eyes to settle on for more than a few moments at a time.

Suleman’s poem asks, “who am i / but the corporeal object / yielded in time” and observes “realising shape shifting / summoning the art of getting through the day / if Allah wills then Allah will”. In response to the invocation of embodiment and navigating space, I recall the Clearing in Toni Morrison’s magnum opus Beloved. Led by matriarchal preacher Baby Suggs, in this reclaimed forest space, formerly enslaved Black people gather to love their own flesh because “They [white society] despise it”; their “flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass”.

The Space Belongs To Them suggests an understanding that the body is a space in of itself, a site on which social scripts are read and recited, where race, gender, sexuality and class are inscribed to determine how and with what degree of comfort and security we can manoeuvre through space.

In that vein, the two opening films in The Space Belongs To Them ask us to consider what it means to listen, not just with your ears, but with your whole self; to respond intuitively to visual and tactile stimuli through your body and to (re-)occupy the physical and cultural spaces that we’ve been alienated from. Produced at a time in New York when Black parents were organising to ensure their children were appropriately nurtured within formal systems (through community control of school boards and Black Power social programmes, for example), the short documentary Statues Hardly Ever Smile (1971) gathers a predominantly Black group of children in the Brooklyn Museum and asks them to creatively respond to the displayed artefacts by improvising drama and dance performances.

We then witness as they play out the Egyptian saga of Osiris and Seth, meditating on the meanings of family, anger, violence, and the inevitably of death alongside the promise of rebirth. Likewise, the fashion film Wata (2020) evokes the West African water spirit Mami Wata, castigated by eurocentric thought as a demonic entity, and features scenes of Black people suspended serenely in water, being embraced in community and dancing to soulful music.

Both Statues Hardly Ever Smile (1971) and Wata (2020) encourage us to look at somatic expression as a means to comfortably, confidently assert our bodies within space. Similarly, Fresh Cutz (2018) and Precious Hair and Beauty (2021) are tender, hilarious accounts of the Black barbershop and hair salon, depicting the many mundanities, absurdities and intimacies that occur during recreation and grooming in communal spaces. In this way, these films are in conversation, contrastingly, with the screening of Ngozi Onwurah’s short film Neighbourhood Alert (2023) at Genesis Cinema. Featuring a Nigerian American family in Los Angeles’ suburbs and their experience of insidious white liberal racism adjacent to police violence, it brilliantly disrupts the suburban spacial ideal of open cul-de-sacs and lush green lawns by holding select shots of mother and son looking through locked front yard gates, suggestive of prison bars.

The themes that Ama and Gikunoo articulate, emphasised through their use of sound, echo across the film festival’s events and are re-expressed in LCC presents: Sick Jazz at the ICA Cinema and Rave Cinema, in the ICA Theatre, both of which fuse performance with cinema, where the music moves the body as we watch, keeping us in sync with the pace of drama, our emotions in tune with pathos. LCC presents: Sick Jazz begins with a live flute and saxophone recital before presenting a trio of films, each soundtracked by jazz music. Set inside a New York City dope house full of jazz musicians, Shirley Clarke’s The Connection (1961) critically depicts a documentary crew growing increasingly frustrated as they attempt to capture a heroin drug deal, taking more and more desperate measures to force the action they wish to film. In that contained space of constructed reality, which produces a sense of claustrophobia, the musicians drift in and out of consciousness, playing their instruments spontaneously as the mounting tension tests honour amongst thieves.

By having DJ Camden play a live electronic dance music set and Heena Song and Julian Hand perform an interactive light show, Rave Cinema moulds the ICA Theatre into a 90s club where we can dance to feel free, just as house music legend Frankie Knuckles has often compared the genre to gospel and the club to the Black church; a space of rhythms, lights, and vibrations permeating into the skin, prompting a soulful sense of transcendence and collectivity. These short films also transport us outside of the enclosed club to the countryside rave, another site of ecstatic embodiment. In Arjuna Neuman’s Syncopated Green (2022), for instance, a clear thread is drawn from classical renditions of the British natural landscape in the National Gallery to rave culture in those same lush environments.